Free running

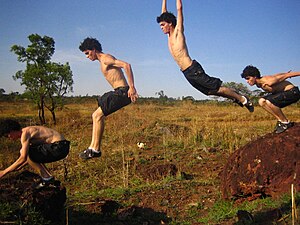

Free running is a physical art, in which participants (freerunners) attempt to pass all obstacles in their path in a smooth and fluid way. Free runners interact with their environment using movements such as vaulting, jumping, somersaults and other acrobatic movements, creating an athletic and aesthetically pleasing way of moving. It is commonly practised at gymnasiums and in urban areas that are cluttered with obstacles.

Overview

Founded by Sébastien Foucan and inspired by the similar art of displacement (parkour) which was founded by Foucan's childhood friend David Belle, free running embraces elements of tricking and street stunts, which are considered by the parkour community to be inefficient and not parkour. Initially, the term free running was used interchangeably with parkour. However, as free runners became interested in aesthetics as well as useful movement, the two became different disciplines. The term free running was created by Guillaume Pelletier and embraced by Foucan to describe his "way" of doing parkour.[1] Foucan summarizes the goals of free running as using the environment to develop yourself and to always keep moving and not go backwards.

While free running and parkour share many common techniques, they have a fundamental difference in philosophy and intention. The aims of parkour are reach, the ability to quickly access areas that would otherwise be inaccessible, and escape, the ability to evade pursuers, which means the main intention is to clear their objects as efficiently as they can while free running emphasises self development by "following your way".[1] Foucan frequently mentions "following your way" in interviews,[2] and the Jump documentaries. He explains that everyone has their way of doing parkour and they shouldn't follow someone else's way of doing it, instead they should do it their way. Free running is commonly misinterpreted as being solely focused on aesthetics and the beauty of the certain vault, jump, etc. Although a lot of free runners choose to focus on aesthetics, that is just "their way", the goal however is still self development. The easiest way to explain the differences between the two activities is that in parkour you try to get from A to B in the most efficient and natural way which could be exercised in case of a real threat, whereas in free running you may employ movements of your choosing. You might also do certain movements solely for their aesthetic value and the challenge of execution. Free running is essentially complete freedom of movement.

There also has been a clash between the Parkour and Free Running communities over the use of different terms for the same vaults. The parkour community generally refers to the vaults by their French terms or the English translation while the free running community headed by the Urban Freeflow website have created new terms such as the "Kong", "Monkey", etc. For example, the vault where one jumps putting their legs between their arms is known in French as the "Saut de Chat", while the English translation is "Cat Jump" though some call it a "rabbit vault" . But the Urban Freeflow site has renamed this vault the "Kong" or "Monkey" Vault.

Another contentious issue that may begin to make a rift between the parkour and free running communities or may actually strengthen their bond is the idea of professional and amateur competition. From the start the parkour community has been always against the idea of serious competition as it violates the foundations of the philosophy of Parkour. The Free Running community is not as strongly decided as a group as to their position on the matter although Sébastien Foucan's thoughts on the matter were revealed, he mentions in an interview with Urban Freeflow that he doesn't like competition and it's not "his way", but it may be someone else's "way".[2] The conflict between Free Running and Parkour occurred when the founders of Parkour, David Belle and Sebastien Foucan included, split up and went their separate ways. David Belle mainly stuck to Parkour as efficiency while Sebastien Foucan focused on the freedom of movement, self-development and aesthetic aspects of Parkour thus making Free Running more popular. Although each sport may be defined differently the two sports share similar commonalities because they were founded by two friends.

History

Sébastien Foucan used the term 'free running' to describe a form of physical exercise that he practised which was showcased in the Channel 4 documentaries Jump London and Jump Britain. The term has been in use since at least the early 1980s when it was used to describe a more adventurous form of jogging where the runner would incorporate a variety of movements transforming a jogging session into a more demanding, enjoyable and expressive physical experience. Jumping and tac-ing obstacles, rolling, and a variety of stretching movements would be used to break the regulated physical patterns of movement involved in basic running/jogging.

Cartwheel – this is begun by extending both arms straight above the head. One foot is pointed in the desired direction of the cartwheel. The arms reach for the floor in symmetry with the foot that is being used for pointing (if pointing with the right foot, reach with the right hand). The other hand follows in this motion, keeping it over the head. As the first hand goes down, the opposite foot goes up in the air. The hands should touch the floor in a straight line. The other leg is lifted by kicking off from the ground. The free runner should already be standing on his/her hands at this point momentarily as the motion continues forward.

For the landing, the first leg that was lifted off—the non-pointing foot—should touch the ground first, followed by the second foot. Let the momentum of the motion flow, taking the hands off the floor which finally brings the runner back to an upright standing position. This should be the same position he or she started in, but with the opposite leg forward.

Roundoff - A roundoff is almost like a cartwheel. The difference is in the landing. After the second hand touches the ground, land on both feet at the same time. The final position should be faced in the opposite direction of the starting position.

Roll - This technique starts from an elevated position. Jump from the elevated area towards the ground while holding the body upright, as if free-falling. Land on both feet with your knees bent, letting the resistance of the ground flow through (not bending your knees will result to serious injury). Then lean the head and either one of your shoulders forward towards the ground. Push off with both feet to roll on the ground using the back. The momentum is enough to carry you back into a standing position coming off the roll, continue moving forward to keep yourself balanced.

Monkey Vault – this can be done either from a static position or a run up to the rail/wall. Grab the obstacle with both hands. The hands should be spaced on the obstacle at more than the shoulder width so that the feet and the rest of the lower body can pass between the hands. Jump on both feet and tuck the knees into the chest. In mid-air, push back with both arms to thrust the body straight forward this then lands you on both feet.

Superman or Dive Roll – Run towards the obstacle. When the obstacle is only about a step away, jump forward on both feet. The midsection should be arched over the obstacle. Hold both arms in front to anticipate the landing in a diving motion. Both hands should land simultaneously before leaning the head forward on the ground. In a smooth motion, the upper back touches the ground and the rest of the body follows in a roll. The momentum should carry you back to a standing position, and continue the run.